By Pete Villasmil

The following analysis was originally written on October 27, 2020 for MEJO 244 (Talk Politics) with Professor Ferrel Guillory. I have included a brief section at the article’s conclusion that evaluates how my thoughts and arguments before the 2020 election hold up six months later in April 2021.

It feels as if the whole political world has been turned on its head ever since businessman Donald Trump stunned the nation with his ascension to the highest office in the land. The unexpected failure of the polls in 2016 prompted a serious distrust in the them. Millions of Americans remain skeptical today on whether they can trust the polls or not. These doubts are often fueled by the president to tarnish the media and the political establishment. While it is apparent polls have had their issues in recent elections, it appears 2020 is the year of their surprising comeback. It needs to be, considering this is the industry’s final chance to prove their worth to their American people. Even though a healthy skepticism is good, Americans should have more confidence in this year’s polls. Due to the reforms that have been put in place and the overall evolution of the industry, 2020’s polls should be trusted in the closing days of this campaign.

To effectively discuss the reliability of the 2020 polls, one must first look back to the success and failures in 2016. Polling predicting the Hilary Clinton and Donald Trump contest was embarrassingly inaccurate especially in regards to some of the best polling organizations in the industry. The New York Times, Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight, Moody’s Analytics, and Larry Sabato’s Crystal Ball all indicated confidently that the former Secretary of State would win decisively against President Trump. The Huffington Post’s election forecast giving Clinton a 98 percent chance of victory still gets ridiculed to this day by passionate polling skeptics.

The overall problem with 2016 was not so much that the national polling was inaccurate; it was quite the contrary, as most national polls did suggest that Clinton would win the popular vote by a 2-3 points, which she accomplished. Instead polling errors in key states, specifically mistakes in how college-educated voters were implemented in polling models, resulted in such a vast discrepancy between the predictions and the results. With the electoral college system that the United States utilizes, these missteps became a major issue. Pew Research suggests that many state-level polls in 2016 failed to include more non-educated voters (who were more likely to support Trump than Clinton), and undecided voters who were leaning towards Trump. These uneducated voters are typically more difficult for pollsters to reach in any normal year, but they faced increased challenges in 2016 due to the “frustration and anti-institutional feelings that drove the Trump campaign [which] may also have aligned with an unwillingness to respond to polls.” As a result, pollsters unknowingly relied on a skewed representative sample and based their models around this faulty sample. Many polls were defective because of this mistake. Further, the decreased dependability of widely-used landline polls and fewer likely voters answering pollsters’ calls also affected the quality of their representative samples. As a whole, 2016’s polling blunder was primarily caused by the slow death of the landline and the overrepresentation of college-educated voters.

The polling fluke from four years ago clearly indicated reforms needed to be put in place in the industry. While we will not be sure until after the election if the changes that have been made were successful, it appears pollsters have attempted to rectify the issues in 2020. For one, many pollsters have now started to “weight” their representative sample, a process where they no longer include more college graduates than there are in the actual electorate, which eliminated an unintentional inflation for Democratic support in the polls. In leveling the sample by “weighting” it, the sample becomes more representative of the electorate and results in more accurate predictions. In addition, the overall model design in elections following 2016 has vastly improved with models now factoring in potential polling errors or sudden swings in public opinion. Polling in 2018’s congressional races indicate that these changes have helped improve the polls’ accuracy, as they predicted the basic outcome of those midterm races that resulted in a Republican Senate and a Democrat House. But 2018 did not redeem the pollsters as much as they would have liked, as Republicans made unexpected gains in Indiana, Missouri, Florida, Tennessee, and Ohio.

There’s also the matter of the “shy Trump voter,” closeted supporters of the president who lie to pollsters, contributing to skewed polls. Despite this political phenomenon not being substantially proven, it may end up playing a bigger role in 2020 than expected if this circumstance is as widespread as some claim. Although pollsters have been unable to definitively state whether they have been able to reach out to these voters, one organization is confident that they have diagnosed and remedied the issue of the “shy Trump voter.” The Trafalgar Group was one of the few organizations to accurately predict Trump’s victory in 2016 and the Republican surge that occurred in Florida in 2018. Robert Cahaly, founder of the organization, claims to have found a way to identify and poll the “shy Trump voter,” and thus has the president currently ahead of Biden in almost all of the battleground states and the Rust Belt. It is a bold claim and its validity will be determined in the weeks following election day, but it is nonetheless a factor to consider on whether polls will succeed this year.

It is also unclear what effects the COVID-19 pandemic may have had on polling in the closing days of the campaign. What is clear is that Biden appears to have the upper hand. The current RealClearPolitics average has the former vice-president up by double digits nationally, and has him comfortably ahead in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin, all states the president needs to capture if he wants to solidify his reelection prospects. Further, it appears as of now that senior citizens and suburban white women, two voting blocs the president was able to rely on in 2016, are breaking for Biden. The situation looks even bleaker for Trump when considering the massive increase in young voter participation, many who are predicted to vote blue. Pollsters have reflected these demographics’ favorability towards liberal candidates. And if Biden is able to succeed in winning in the decisive way polls are predicting, it is likely that Americans will find a new sense of confidence in polling once more. On the other hand, a major Trump victory would present a nightmare scenario for the industry, one that results in the destruction of the remaining trust Americans have in polling. As warned by GOP pollster Frank Luntz, it would be difficult for the average American after this year to take any poll seriously if the president manages to acquire more than 300 electoral votes. It is a situation that has been given a one to two percent chance in likelihood, but if 2016 proved anything, it is that anything is possible despite what the polls say.

The dramatic reality is that the future of polling depends on this election, and pollsters are depending on a Biden victory to regain the credibility they have lost. The last general election reminded people that pollsters are not divine political prophets, but hopefully they can once again claim a respected status after November. Until then, all Americans can do is wait, see, and vote.

April 2021 Commentary

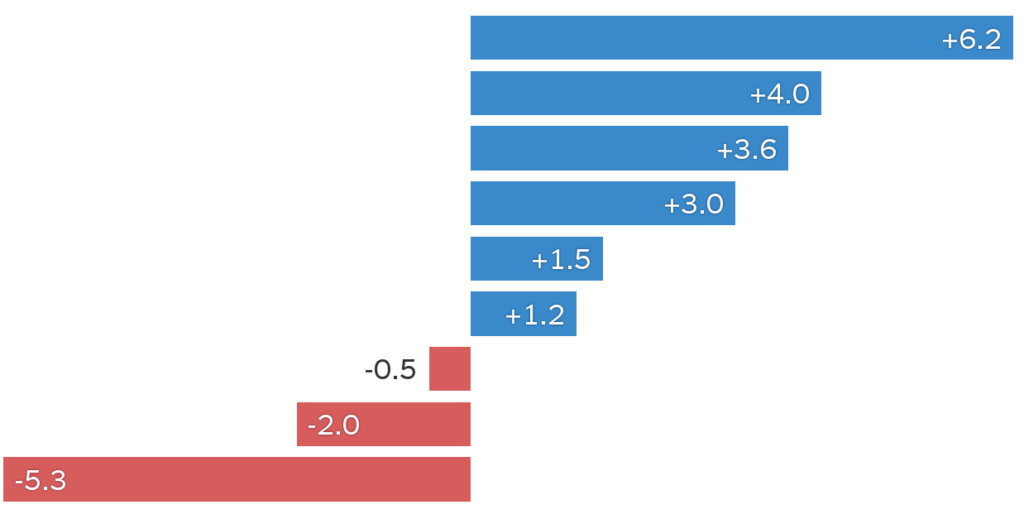

Looking back, I realize my prediction for the overall accuracy of 2020 polling was too optimistic. While the polls did accurately indicate the overall winner of the general election, they failed miserably in presenting how popular Donald Trump was in battleground state like Florida, Ohio, and even Texas. I, like many others, took pollsters and other organizations at their word when they proudly claimed these reforms were sufficient in providing a more accurate estimate of the election outcome. While that faith may have been misplaced, I believe the overall situation can serve as an important reminder that polls are simply educated guesses. They are not, and have never been, absolute. I think I realize this more now than I did in the height of the 2020 campaign. 538’s Nate Silver echoed a similar sentiment in his post-election analysis stating, “Voters and the media need to recalibrate their expectations around polls — not necessarily because anything’s changed, but because those expectations demanded an unrealistic level of precision.”

Further, I believe now more than ever that the hidden Trump vote was present in November and not as elusive or mythical as other experts may have indicated. The GOP’s poor performance in the Georgia runoff in January has also convinced me of this. While I only briefly mentioned the Trafalgar Group, they ended up having a very successful night on Nov. 6, likely because of their claimed ability to gauge this portion of the voting population. I feel certain that without this voting bloc, the former president would not have been as successful in the states he did manage to carry.

Ultimately, this leaves the polling industry in a very difficult position. In retrospect, I realize I painted a very grim picture of what would occur if the pollsters got it wrong for a second time. In actuality, I genuinely do not think they will ever disappear from the political and reporting processes. But something has to change, whether it is the way the polls are conducted, how we in the public interpret them, or the manner in which the media reports on them. One thing is for sure, all eyes are on 2022. The upcoming midterm will no doubt be a supremely consequential year for both the political make-up in Capitol Hill and the polling industry. For now, we will all just have to manage our expectations.